A Student's Guide to Software Engineering Tools & Techniques »

Introduction to Linux Bash Shell

Author: Wang Junming

Reviewers: Rahul Rajesh, Ong Shu Peng, Jeremy Choo, Tan Zhen Yong

What is the Shell?

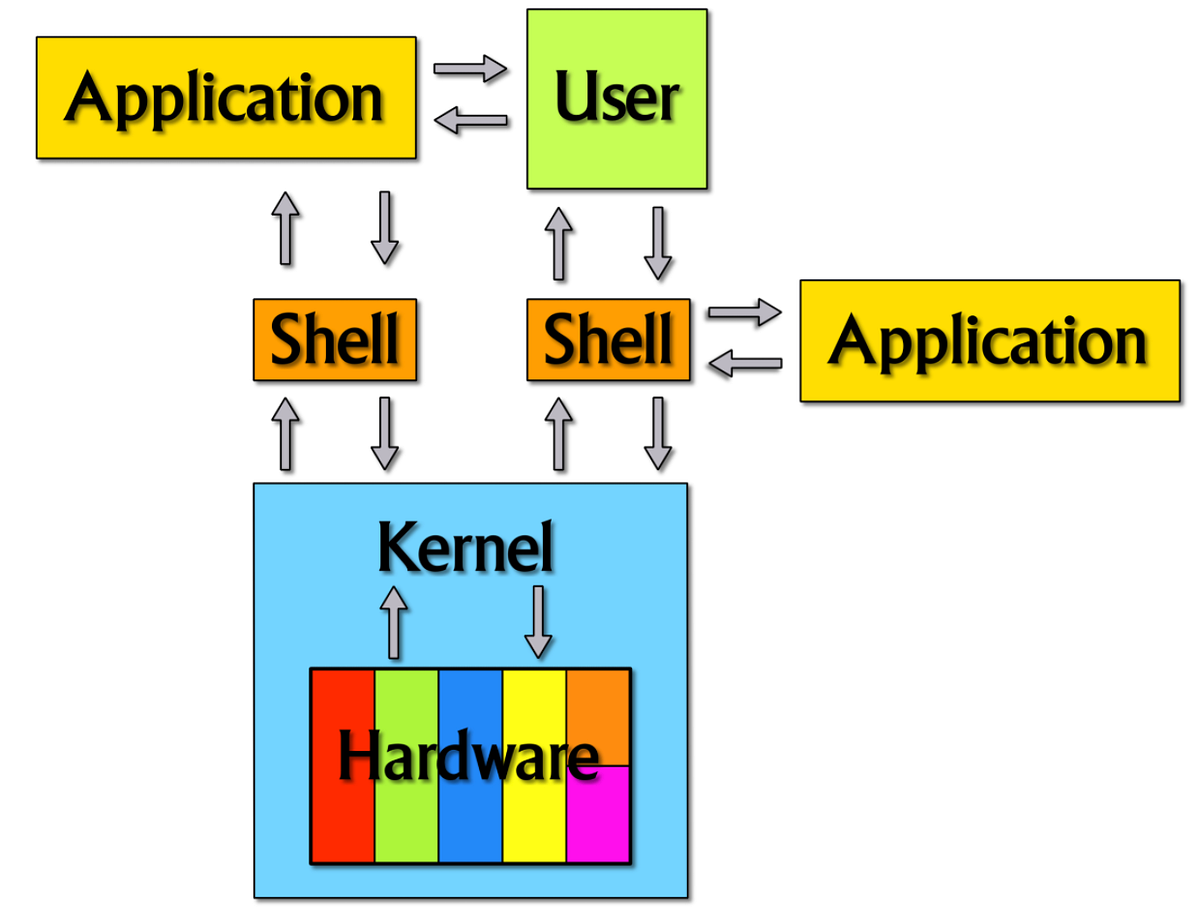

In general, a computer can be divided into 3 abstraction layers: hardware, kernel and applications. As users, we cannot control the hardware directly. Instructions have to be given through the kernel as the kernel is the one that controls the hardware.

source of image: What (really) happens when you type ls -l in the shell

The shell is the interface through which we pass instructions to the kernel. These instructions will then be executed through the hardware. In this article, we will look specifically into the Linux bash shell.

bash stands for Bourne Again SHell, an enhanced version of the original Unix Shell program. It has become the standard shell of various linux distributions.

source of image: The Best Keyboard Shortcuts for Bash

Users interact with the bash shell using various commands. A command is an instruction that is used to execute a specific function. The functions that a command is able to execute range from file/directory manipulation, process management to even networking! You can also combine different commands to carry out complex operations.

One of the most widely used command is ls, which lists out all the files under the current directory. Here is a video demonstration of the ls command in action:

Bash Scripts

Bash supports a powerful language for writing scripts, usually referred to as bash scripts.

Bash scripts are able to carry out a range of operations by executing different commands. Let us consider an example: suppose you want to check if a given file exists. The following script will be able to do that; you input the filename and it will tell you the answer.

#!/bin/bash

echo -e "Please input a filename, I will check if the file exists.\n"

# waiting for user input.

read -p "Input a filename : " filename

# check if file exists.

test ! -e $filename && echo "The file '$filename' DO NOT EXIST" && exit 0

test -f $filename && filetype="regular file"

test -d $filename && filetype="directory"

# output result.

echo "The file: $filename is a $filetype"

Here is an video demonstration of running the script.

The above bash script is still just a collection of bash commands; this means you can get the same result by typing those commands one at a time. However, the true advantage of using a bash script is due to its support for conditionals, loops and functions.

The following is an example of a bash script that make use of conditionals and loops. Suppose you want to let the user input a directory name, check if it exists, and then output the write permission for all files inside that directory.

#!bin/bash

# read user input and check if directory exists.

read -p "Please enter a directory name: " dir

if [ "$dir" == "" -o ! -d "$dir" ]; then

echo "The $dir is NOT exist in your system"

exit 1

fi

# output permissions for each of the file under the directory.

filelist=$(ls $dir)

for filename in $filelist

do

perm="readable"

test -w "$dir/$filename" && perm="$perm writable"

echo "The file $dir/$filename 's permission is $perm"

done

Here is an video demonstration of the script in action.

Functions in bash scripts are just like functions in normal programming languages. More information about bash scripts can be found here.

Combining of Scripts via Stream Redirection

In Linux, you can redirect the output of one application to the input of another, combining the two applications together as if there is a pipe between them. In fact, Linux can pipe data between programs, files, and input/output devices seamlessly. You can take advantage of these abilities in your shell commands/scripts to perform complex tasks with just a few commands.

For example, suppose you wrote an executable calculate that takes in a user input, does a calculation, and gives the output. To run it, you simply type:

./calculate

However, you do not want to manually test this program. Instead, you want to test with a larger data set known as DataBundle. You verify the output with another executable verify, which takes in the result as input, verifies its correctness and outputs PASS or FAIL. Here's how we can do it.

./calculate < DataBundle > result

./verify < result

Notice in this case, calculate uses the data in DataBundle as input, and output the results to the file result. Then, result is taken as input to verify, and the final verification result is printed on screen.

Furthermore, if the code of calculate is buggy, it throws an exception and the error message will be redirected to the error output. As a result, our result file will be empty! In order to handle this properly, we can also redirect our error output to a file errors, and verify that it is empty (so that no errors have occurred during execution) before we execute verify.

#!/bin/bash

./calculate < DataBundle > result 2> errors

if [ -s errors ]

then

./verify < result

else

echo "error occured during execution."

fi

Furthermore, you can use the | symbol to chain various Linux commands together such that the output of the previous commands is passed as input to the next command.

The following example make use of shell commands ps and grep. ps displays information about a selection of the active processes and grep searches for the pattern in the given input.

Let us say you want to check the status of process p running on your system. The ps aux command by itself lists all the processes currently running. If there are too many processes listed and you cannot find p, you can pass the result of ps aux to grep 'p' to as ps aux | grep 'p' to capture process p's status.

A more detailed introduction to I/O stream redirection can be found here.

Why Use the Shell?

A common question many people ask is: Why type commands in a shell when we can do the same things using GUI applications? Here are some reasons:

- Faster: Often, performing a task via the shell is faster than doing the same via a GUI application. This is because the shell does not get slowed down by other factors like GUI rendering. For example, when performing tasks on a remote server using a shell, the lag will be less.

- Uniform: Unlike GUI apps whose availability and usage can vary between Linux distributions, the shell is always available and the usage is almost the same across different Linux distributions.

- More powerful: GUIs tends to simplify things, giving the user fewer options. With a shell, you will have complete control of every option. While the shell has a steep learning curve, once you are familiar with it, you can do more things efficiently as compared to a GUI application. For example, you can automate things with a shell, something not easy to do with a GUI application.

How to Get Started?

In our opinion, there is no need to learn the shell in one go. Instead, whenever you use a GUI tool to accomplish a task, try to learn how to do the same using the shell. For example, when using git, use it via the shell instead of a GUI tool such as Source Tree. That way, you can learn the shell incrementally, over time.

However, if you really wish to learn bash systematically, below are some resources you might find useful.

- Bash Reference Manual is a good reference manual of linux bash shell.

- The Google Shell Style Guide is a good baseline for good shell scripting style.

- Gentoo has a good

bashshell reference. - Apple's Shell Scripting Primer is a in-depth introduction to shell scripting for beginners.

In addition, you can always use the man command to find more information about a bash command. For example, the command man grep will give you the built-in help page about the grep command. These help pages are written in a programmer-friendly format and are very comprehensive.

Below is an example showing the man page for grep command.

GREP(1) BSD General Commands Manual GREP(1)

NAME

grep, egrep, fgrep, zgrep, zegrep, zfgrep -- file pattern searcher

SYNOPSIS

grep [-abcdDEFGHhIiJLlmnOopqRSsUVvwxZ] [-A num] [-B num] [-C[num]]

[-e pattern] [-f file] [--binary-files=value] [--color[=when]]

[--colour[=when]] [--context[=num]] [--label] [--line-buffered]

[--null] [pattern] [file ...]

DESCRIPTION

The grep utility searches any given input files, selecting lines that

match one or more patterns. By default, a pattern matches an input line

if the regular expression (RE) in the pattern matches the input line

without its trailing newline. An empty expression matches every line.

Each input line that matches at least one of the patterns is written to

the standard output ......